Authored by Alex Berenson via ‘Unreported Truths’ substack,

Federal efforts to censor social media extend past discussions with companies like YouTube over broad guidelines about Covid-19 “misinformation” to specific demands for suppression of individual posts, an email from an FDA official reveals.

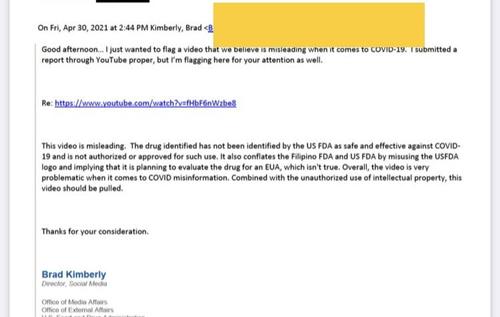

In the April 30 email, the Food and Drug Administration director of social media, Brad Kimberly, told a Google lobbyist about that the agency expected YouTube to pull a video touting the potential of a new monoclonal antibody treatment for Covid. (Google owns YouTube.)

“Overall, the video is very problematic when it comes to COVID misinformation,” Kimberly wrote to the lobbyist, Jan Fowler Antonaros.

“This video should be pulled.”

YouTube initially declined to remove the video. However, it has since been taken offline.

How often the FDA has made other censorship demands is unknown, because the agency is apparently hiding the existence of its efforts in response to Freedom of Information Act requests.

In October, I asked the FDA and several government agencies to disclose both their internal discussions about me and their communications with social media companies like Twitter and YouTube about censoring Covid “misinformation” in general.

On Nov. 30, the FDA responded it had found some emails about me – mainly in response to questions I had asked in April and May for a story about VAERS, the federal vaccine adverse events reporting system. But FDA said it could not find any emails between its officials and social media companies that met my request.

Yet at the bottom of the emails containing the agency’s discussions about me was the email between Kimberly and Antonaros – apparently attached there by accident, as it had nothing to do with me.

* * *

The monoclonal antibody, leronlimab, is being developed by a small and troubled drug company called CytoDyn, whose stock trades around $1 a share. CytoDyn has repeatedly touted leronlimab, but clinical trial results suggest the drug is useless against Covid.

In May the FDA publicly stated “the data currently available do not support the clinical benefit of leronlimab for the treatment of COVID-19” and said it had no plans to approve the drug. (SOURCE: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/statement-leronl…)

Because leronlimab remains unapproved, it is effectively unavailable to patients. Thus whatever its potential side effects or lack of effectiveness, it is not actually a risk to anyone – except Cytodyn’s investors, who are not the FDA’s concern.

In response to Kimberly’s email, Antonaros responded on May 6 that YouTube had reviewed the video and found it did NOT violate the company’s guidelines – probably because it did not promise the leronlimab would cure Covid, only touted its potential and encouraged the FDA to allow it under an emergency use authorization.

Yet the video has since disappeared from YouTube. It is now available only at the Internet Archive.

(SOURCE: https://web.archive.org/web/20211024082638/)

* * *

It is easy to understand the FDA’s frustration with leronlimab and CytoDyn.

But corporate and patient campaigns designed to push the agency to approve new treatments (sometimes of marginal or no value) are common and long predate Covid. Ultimately, the agency has the final authority on whether a drug can be sold and prescribed in the United States, no matter how much a company complains.

What is new is the agency’s efforts to scrub such campaigns from the Internet.

And, apparently, to pretend it is not doing so. My initial Freedom of Information request to the FDA included a request that the agency provide:

Any email or other communications between any FDA officials to executives, managers, or other employees at Twitter, Facebook and its subsidiary Instagram, and Google and its subsidiary YouTube regarding COVID and Sars-Cov-2, including BUT NOT LIMITED TO efforts to shape public opinion around lockdowns and vaccines and the anti-“misinformation” enforcement efforts of the five social media platforms mentioned above.

Yet the agency said it had not found a single record responsive to that request – not one – even as it accidentally provided one.