Source: Zero Hedge

Authored by Brad Polumbo via The Foundation for Economic Education,

Founding father and the second president of the United States John Adams once said that “Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passion, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.” What he meant was that objective, raw numbers don’t lie—and this remains true hundreds of years later.

We just got yet another example. A new data analysis from Harvard University, Brown University, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation calculates how different employment levels have been impacted during the pandemic to date. The findings reveal that government lockdown orders devastated workers at the bottom of the financial food chain but left the upper-tier actually better off.

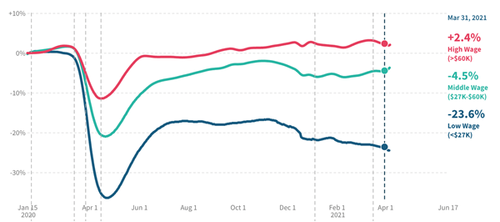

The analysis examined employment levels in January 2020, before the coronavirus spread widely and before lockdown orders and other restrictions on the economy were implemented. It compared them to employment figures from March 31, 2021.

The picture painted by this comparison is one of working-class destruction.

Employment for lower-wage workers, defined as earning less than $27,000 annually, declined by a whopping 23.6 percent over the time period. Employment for middle-wage workers, defined as earning from $27,000 to $60,000, declined by a modest 4.5 percent. However, employment for high-wage workers, defined as earning more than $60,000, actually increased 2.4 percent over the measured time period despite the country’s economic turmoil.

The data are damning. They offer yet another reminder that government lockdowns hurt most those who could least afford it.

Image Credit: tracktherecovery.org

Some critics argue that the pandemic, not government lockdowns, are the true source of this economic duress. While there’s no doubt the virus itself played some role, government lockdowns were undoubtedly the single biggest factor. It’s pretty intuitive that ordering people not to patronize businesses and criminalizing peoples’ livelihoods would hurt the economy. This intuition is confirmed by data and studies showing as much. And don’t forget the fact that heavy lockdown states have consistently had much higher unemployment rates than states that took a more laissez-faire approach.

Others might insist that the mitigation of the spread of COVID-19 accomplished by lockdowns justifies this economic fallout. But this argument fails to account for the many peer-reviewed studies showing lockdown orders did not effectively slow the pandemic’s spread, or the painfully inconvenient fact that most COVID-19 spread occurred not in workplaces, restaurants, or gyms but at home. (Making “stay-at-home orders” seem like an astonishing mistake in hindsight.)

So, all lockdowns really seem to have accomplished is at best a mild delay in the pandemic’s trajectory in exchange for a host of lethal unintended consequences such as a mental health crisis and skyrocketing drug overdoses. And, as we now know, a highly regressive economic fallout for the working class.

Of course, Ivy League researchers almost certainly did not intend to expose the failings of big government pandemic policies when they set out to catalog employment data. But, as Adams said, facts are stubborn things.