Source: Zero Hedge

In Wednesday’s press conference, Jay Powell confirmed that the Fed is setting off on a historic experiment: welcoming a conflagration of red-hot inflation for an indefinite period of time in an overheating economy, with the underlying assumption that it’s all “transitory” and that inflation will return to normal in a few years, and certainly before 2023 when the Fed’s rates will still be at zero.

There is a big problem with that assumption: while FOMC members, most of whom are independently wealthy and can just charge their Fed card for any day to day purchases of “non-core” CPI basket items, the vast majority of the population does not have the luxury of having someone else pay for their purchases or looking beyond the current period of runaway inflation, which will certainly crush the purchasing power of the American consumer, especially once producers of intermediate goods start hiking prices even more and passing through inflation.

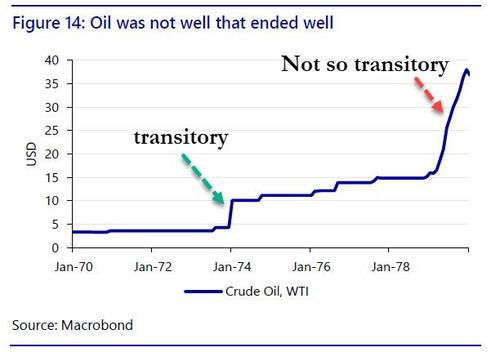

Many readers may not recall, but one such instance of “transitory” inflation that proved to be anything but and led to the infamous Volcker Fed and its double digit rate hikes, was the price of oil which took off in the Arab oil embargo and then refused to come back for over a decade.

The Powell Fed, however, is eager to brush aside any analogues to previous episodes of runaway inflation which it sees as having a demand component, and merely ascribes what is taking place to unprecedented supply chain disruptions – i.e., collapse in supply – as a result of both the trade war with China and, more recently, the covid pandemic, which have unleashed chaos among traditional supply-chain intermediaries.

To be sure, the Fed is certainly right that there has been turmoil within virtually all supply chains: one needs to only read what the respondents to the most recent mfg ISM said to get a sense of how bad it truly is:

- “Things are now out of control. Everything is a mess, and we are seeing wide-scale shortages.” (Electrical Equipment, Appliances & Components)

- “Supply chains are depleted; inventories up and down the supply chain are empty. Lead times increasing, prices increasing, [and] demand increasing. Deep freeze in the Gulf Coast expected to extend duration of shortages.” (Chemical Products)

- “The coronavirus [COVID-19] pandemic is affecting us in terms of getting material to build from local and our overseas third- and fourth-tier suppliers. Suppliers are complaining of [a lack of] available resources [people] for manufacturing, creating major delivery issues.” (Computer & Electronic Products)

- “We have seen our new-order log increase by 40 percent over the last two months. We are overloaded with orders and do not have the personnel to get product out the door on schedule.” (Primary Metals)

- “A sense of urgency is being felt regarding new orders. Customers are giving an impression that a presence of stability is forthcoming and order flow is increasing.” (Textile Mills)

- “Prices are rising so rapidly that many are wondering if [the situation] is sustainable. Shortages have the industry concerned for supply going forward, at least deep into the second quarter.” (Wood Products)

- “We have experienced a higher rate of delinquent shipments from our ingredient suppliers in the last month. We are still struggling keeping our production lines fully manned. We anticipate a fast and large order surge in the food-service sector as restaurants open back up.” (Food, Beverage & Tobacco Products)

- “Steel prices have increased significantly in recent months, driving costs up from our suppliers and on proposals for new work that we are bidding. In addition, the tariffs and anti-dumping fees/penalties incurred by international mills/suppliers are being passed on to us.” (Transportation Equipment)

Even BofA’s Chief Investment Officer, Michael Hartnett, threw in the following “heard on main street” anecdote in one of his recent Flow Show notes:

“Our worldwide supply chain, and ability to provide products and services to you, is being significantly impacted by increased prices resulting from labor and raw material shortages, escalating raw material prices, manufacturing delays and transit interruptions. Stated directly, our costs are increasing and are much more volatile than in the past.” – Mar 3rd price increase notification to CA real estate developer.

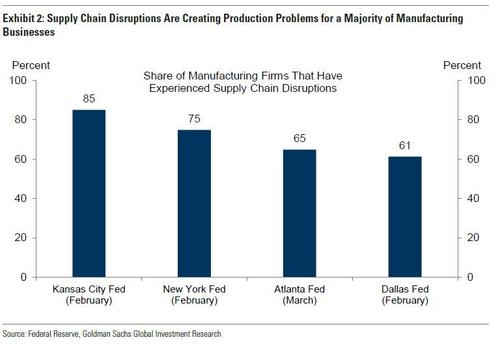

The problem has become so acute that several of the regional Fed business surveys asked specific questions about supply chain disruptions in the last few months. As the chart below shows, a majority of manufacturing firms report that supply chain disruptions are currently negatively affecting production. Additionally, 38% of businesses in the Atlanta Fed’s survey reported that supplier delays were moderate to severe, while 49% of Dallas Fed respondents reported that disruptions had meaningfully raised input prices. In the NY Fed’s Empire Manufacturing Survey, 59% of respondents reported finding new suppliers due to supply chain disruptions, while 58% reported that they had started building extra inventories. Overall, these measures suggest that supply chain disruptions are dramatically and adversely impacting business operations, and leading to far higher prices.

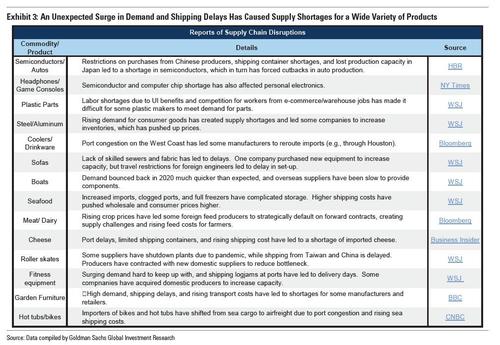

If that wasn’t enough, to better understand the cause of supply chain disruptions, in a recent report from Goldman Sachs the bank summarizes recent media reports on disruptions.

One striking feature of these reports is that supply chain disruptions are “very widespread” and although the semiconductor shortage and its drag on auto production has garnered significant attention, Goldman economist Jan Hatzius notes that many other consumer goods – from headphones to sofas to roller skates – have also faced supply challenges this year.

Digging deeper, Goldman then notes that although supply shortages have affected a wide variety of products, in most cases the root causes are the same:

- First, manufacturers were caught off guard by a faster-than-anticipated recovery in demand and hadn’t ordered enough inputs in advance to meet production needs.

- Second, the increase in goods demand while transportation services are limited by the virus has led to an undersupply of shipping containers and congestion problems at West Coast ports, resulting in lengthy shipping delays.

So first the bad news: even if the current burst of inflation is truly “transitory” – as the Fed vows, staking what little credibility it has that inflation will reverse in the second half of 2021 – Goldman concedes that “neither of the above two problems should abate soon” since fiscal support for household income should keep goods demand elevated and the virus should continue to disrupt the supply of international goods transport services until widespread inoculation in the US and its trade partners normalizes both goods demand and supply.

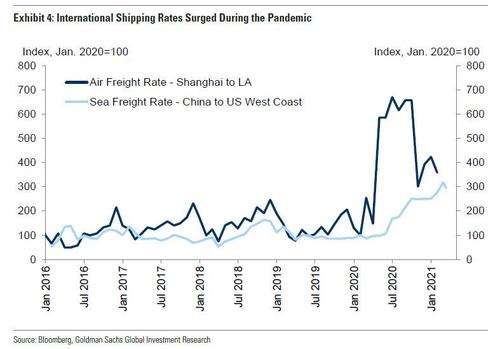

But there is a silver lining: The good news is that because supply challenges are largely driven by transportation and not production constraints—unlike last spring when supplier delays spiked due to factory shutdowns that halted the supply of intermediate goods—Goldman, and by extension the Fed, expects that supply constraints will put upward pressure on prices but have less of an impact on real economic activity. As examples of how some importers and manufacturers have alleviated bottlenecks at higher costs, some companies have started importing bike parts and hot tubs by air rather than sea freight, and other producers have started rerouting imports through alternate ports.

That said, these bottlenecks can lead to another perverse price increase as they substantially increase transport costs in strained trade routes. As shown in the next chart, shipping costs from China to the US have roughly tripled over the last year. This will likely put upward pressure on consumer prices as manufacturers pass these costs on to consumers.

However, according to Goldman, the impact on consumer prices is likely to be muted compared to the huge increases in certain shipping costs, for two reasons.

- First, shipping costs outside of East Asia have seen much smaller increases. For example, domestic transportation costs according to the Producer Price Index – which make up roughly three-fourths of total shipping costs for manufactured goods – are up just 1.6% relative to pre-virus levels.

- Second, total shipping costs represent only a small share of the final price of a good. Using information from the World Input-Output Tables, shipping costs make up less than 3% of the final cost of manufacturing output, implying that international shipping costs make up less than 1%.

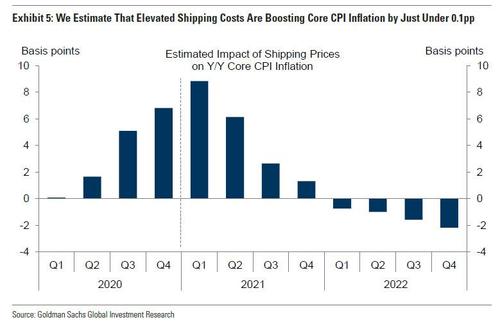

Taken together, Goldman estimates that elevated shipping costs are currently boosting year-over-year core consumer price inflation by roughly 9%!

Goldman’s conclusion is that while supply-chain and logistical challenges will persist and shipping costs will remain elevated until early 2022, putting upward pressure on the level of consumer prices through the end of this year, the bank believes that the impact on inflation has already peaked and will turn into an outright drag in 2022 as shipping bottlenecks resolve themselves and prices moderate.

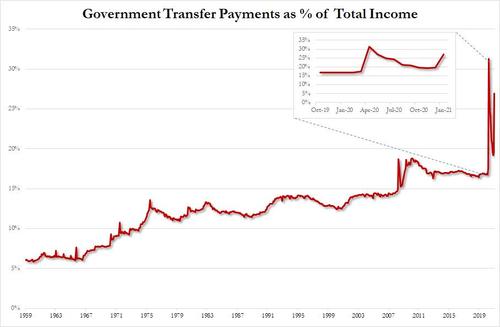

It is this fundamental assumption that none other than the Fed is also betting on; and while Goldman may be right and the supply side of the CPI equation may soon start to normalize and in fact be a drag on Y/Y prices in 2022, the bigger question is how much of an impact does the demand side have, a demand side where, as a reminder, the various stimulus checks have already more than offset all the lost income from the covid pandemic. And much more is coming. In other words, yes – if inflation was purely a supply phenomenon, Powell’s avoidance of surging prices would be justified. But if the increasingly broader acceptance of Universal Basic Income in the form of weekly and monthly stimmies from the government makes handouts from the government, which now accounts for 27% of all consumer income…

… is here to stay, all bets are off, and the Fed has just begun the most ruinous monetary experiment in US history.